Jin-Sun Yoon

The Perfect Little Racist: Reconciliation as a Korean-Canadian

Jin-Sun Yoon is a Teaching Professor in the School of Child and Youth Care at the University of Victoria and was awarded a 3M National Teaching Fellow in 2015. She gave a keynote speech at the Vancouver Korean-Canadian Scholarship Foundation in September 2015.

The perfect little racist: Reconciliation as a Korean-Canadian

This is the working title of one of the chapters that I am writing for my upcoming book. It is catchy and alarming, however, it is true and I am sure many of you can relate (in secret shame).

I am a very busy person and I tend to gravitate towards keeping myself busy and productive…with people, planning, projects, and places. But when I was in my mid-20’s I was held captive for 7 days aboard a Trans-Siberia train. After having read everything I brought and exhausting my limited Mandarin with the Chinese engineers in my car (I was a cool traveler in 4th class), I finally slowed down and thought about my life as a Korean-Canadian. I reflected upon my childhood in a working class white suburb of Vancouver and how I had been shamefully a “perfect little racist.” “Perfect” because it was unsuspected and “little racist” because children absorb the unspoken attitudes of the world around them.

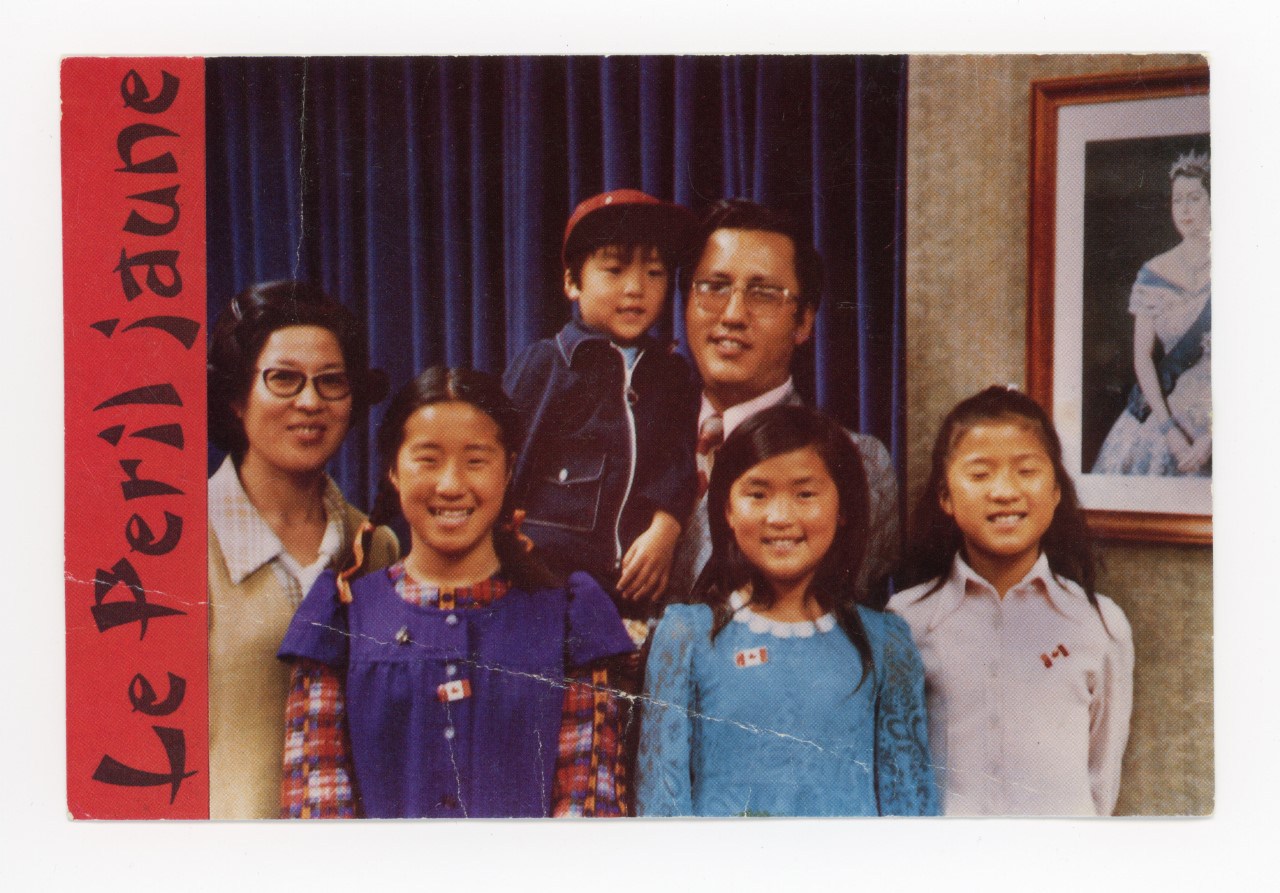

Let me give you some context. I came to Canada when I was 5 with my parents and two sisters, I was the middle child. We came when Canada’s immigration laws changed in 1967 when it went from the unspoken “preferential countries system” to the “point system.” Our parents were born during the Japanese occupation so they had Japanese names and only wrote and spoke in Japanese in grade school. I found out recently that they learned how to read and write in hangul only when they were liberated from the Japanese (that is how much fear there was in being caught writing in Korean)! When my parents were 15, the Korean War broke out and when it ended they were 18. With their education disrupted by the terrible war, they wrote their sat exams and were both placed in medical school.

My father was particularly enamored with all things Western because the Americans had essentially occupied what is known as the Republic of Korea (South Korea). He defied his arranged marriage and wanted a “love” marriage to my mother (this caused a dramatic 72 hour hunger strike to protest his parents’ initial refusal). Then came 3 babies, two years apart, but all girls (which was good for my mom because her mother-in-law had a dream that unless she had 3 daughters, my father’s life would come to an early end!). Meanwhile, most Koreans felt sorry for my mother as she did not have a boy child. Our precious baby brother was born in Canada. He was viewed as the “real” Canadian in our family (the rest of us became citizens when I was 10 years old).

Now, you should know that there was no Multiculturalism policy or even a whiff of the Act (that would finally come in 1988). What it meant was that as a racialized immigrant kid in a very white Canada (at the time), I was given an English name by the United Church minister and essentially expected to assimilate to Canadian (anglo) norms. What they didn’t say was that Canada was a settler-nation that had a narrative of colonial domination. What people didn’t realize was that Canada was created on stolen lands of the Indigenous peoples. As racialized immigrants, we had to “blend in” and try to be “good Canadians,” which meant that we had to adopt “the white ways.” No one ever says that, but children pick it up unconsciously if not consciously.

I can’t tell you how painful “Canada150” was for me, especially with all the hype on July 1st, 2017. I spent the afternoon with 3 generations of a First Nations family to celebrate a house warming, which was a much more comfortable way for me to spend that day. What does 150 years of the nation state (that we call Canada) actually mean to me as a Korean-Canadian? It means that culturally and ethnically I am Korean (with ancestors and relatives still in Korea), but that I have citizenship in Canada. What does that actually mean to me in my daily life?

It means that I have to be ever mindful that I am an uninvited guest (settler) on Coast Salish territories and that the Indigenous people continue to suffer from settler’s collective privileges and gains. Settlers have not taken care of the land and we have used it as a commodity to gain pleasure and profit. As Koreans, we have neglected our ancestral knowledge of our relationship with the land and all creatures. Most of us have become capitalists and consumers without thinking about how colonial we have become. I think of this every day and how I came to be so vulnerable and sensitive to all of this.

I am so ashamed to say that I was a perfect little racist child growing up in Canada in the 60’s and 70’s. I prayed to God that I would become blond and blue-eyed (the perfect human). I loathed my skin turning brown in the summer and valued the porcelain skin of my white friends. I was a traitor to my own family and tight Korean community (in the early “pioneer” days); they were wonderful, but I was so embarrassed to be seen with them in public. I valued all things “white” and uncritically accepted the gross stereotypes of anyone not appearing white. Everything I did was motivated by wanting to belong to a country that I was so proud to be a part of, which meant that I had to be white-identified if not white-skinned. But trust me, I got my fair share of racism towards me so that I could internalize it and dump on more vulnerable people.

Obviously, I could never be white-skinned, but, I could act white and show my disdain for “immigrants” (they could have been Canadian citizens) who spoke “their language” in public, or ate “smelly food,” or wore “funny costumes,” or…you get the gist. I was absolutely intolerant of anything other than the white norm. I gave up Korean but thank goodness that my mother did not. She only spoke Korean to me so it lodged itself deep into my psyche. I went to reclaim it when I learned about the colonial history of Canada when I went to the University of British Columbia to do my undergraduate degree. After that, I dedicated myself to learning about and fighting racism and to teaching social justice. I have been a university professor for almost 2 decades and it is that little racist girl in me that reminds me of how easy it is to be seduced by white supremacy. Canada is not a white country, it is a country that is made up of immigrants who have shown great disrespect and disregard for its original peoples and the land. We, as Korean-Canadians are implicated in that and must reconcile as individuals and as diasporic communities.

I do not want to be one of those immigrants who become a Canadian citizen at the cost of the Indigenous peoples’ equality and fair treatment. I want to be a citizen who faces the inner racist, because that’s what we become when we do not gain consciousness. No one would ever have guessed that the cute little Korean girl was a raging racist who internalized all the racism of the white world around her. I see it all now as the ideal way to exemplify being the “model minority”! Unfortunately, racist systems, institutions, policies, and practices persist even though conversations of reconciliation are taking place. That is only a marginal comfort for Indigenous people.

So, back to that train ride across the Trans-Siberia…it was there that I realized that I had to go to graduate school to find out why I had been such a perfect little racist. Children absorb societal messages. I had not learned racism from my parents, but from my white neighbours, coaches, teachers, librarians, store keepers, police, politicians, etc. My parents did the best they could to create a safe and loving home, but they could not protect us from the insidious racist attitudes that their middle child adopted. In fact, they never even told us anything about Japanese colonization as they did not want us to be prejudiced towards Japanese people. They wanted to raise us in peace and harmony, and that is what Canada felt like for them. Little did we know that it wasn’t like that for Indigenous people whose lands had been infested with the likes of us as we joined the old stock white settlers in occupying and destroying their lands.

As Koreans in Canada, we must acknowledge the struggles of our people under the Japanese annexation and throughout its tumultuous history. Our parents, grandparents, and great grandparents have a very difficult time talking about those days. There is so much shame, pain, trauma, and hurt that come with the stories. When I started to listen to their stories, it gave me insights into the experiences of the Indigenous people with their 500+ years of colonial history. Canada 150 has been hard to celebrate, but I hope that it inspires us to think of the next 150 years and the generations to whom we will be ancestors. What can we be proud to leave for our future generations, not just the next one but for the great-great-great-great-great grandchildren. Will we be proud of what we have done for them by standing together with Indigenous peoples or will we be put in the memories as model minorities or perfect little racists?

Additional Article:

Passion for Social Change Recognized with National Teaching Award, University of Victoria. 27 Feb 2015, Kate Hildebrandt.

https://www.uvic.ca/news/topics/2015+3m-teaching-award-for-jin-sun-yoon+ring