George F. Bruce (1897-1985)

George F. Bruce (1897-1985): A Visionary Adventurer with an Unyielding Dedication to Education

By Gloria Kim

George Bruce held various jobs as a newspaper delivery boy, grocery store employee, sailor on the Great Lakes for a ship that ran from what is now Thunder Bay to Collingwood, and schoolteacher in Alberta before he and his wife, Ellen Bruce (née Tate), volunteered to serve in the overseas mission of the United Church of Canada. His initial interest was in West China, but he and his wife graciously accepted a post in Korea based on the needs of the mission. Shortly after graduating from Queen’s University, George spent two years intensively learning Korean in Hamheung, a city now located in North Korea. Thereafter, he dedicated most of his time in Korea to a Boys’ High School in Lungchingtsun, Manchuria called Eun Jin Academy where he served as the Principal of the school for a decade. Lungchingtsun was then largely populated by Koreans, who had fled the Japanese occupation in Korea. The school was composed of years one to four, and the enrolment fluctuated based on the ability of the students’ families to afford tuition. At first, the school staff considered admitting even the latecomers to the entrance examination, but as the years passed, the type of students admitted steadily improved, as well as the educational program. During the highest enrollment period, close to 400 students attended the school.

In addition to teaching and taking care of administrative matters, George monitored the construction of the school based on the need for space, as well as repairs for the upkeep of the building. Even in the midst of financial cuts and staff shortage, he was determined to do his best and took great efforts to balance the expense of the school with adequate facilities and quality teachers. Furthermore, he initiated the creation of a school for girls and looked after the construction of the Bible Institute Buildings, which provided accommodation for over 70 dormitory students and classroom accommodation for about 200 students.

George was a visionary. He envisioned education flourishing in Korea, people of all races and religions coming together, and Koreans’ taking charge of their own affairs. While he was grounded in the realities of financial strain and staff shortage, he continued to dream of “a whole new plant for [the] school” and of the establishment of a building fund. He saw great promise in the education sphere, and welcomed the new neighbourhoods that sprang up around Lungchingtsun. George organized a night school for English to bring together non-Christian men, and especially Korean, Japanese, and Chinese men. In his letter to a correspondent in Canada, George mentioned his regret at having no Chinese men in his newly opened night school. He believed that contacts and connections facilitated understanding of one another, and reached out to local churches and the Japanese authorities. On one occasion, George managed to work with the Japanese authorities to develop an arrangement where an impending railway construction would not interfere with the operations of the school for girls. George was comfortable taking charge of the complex issues concerning the Eun Jin Academy (many issues were left for him to handle upon his return from his furlough), but he ultimately encouraged the takeover of the school by a Korean man. George’s humility is exhibited through his act of stepping down as Principal to hand over the reigns of the school. Even after his resignation as Principal, he taught at the Eun Jin Academy until he departed Korea.

“…I do hold in high esteem those great men who have gone before me, and who had such splendid vision of the possibilities of this station.”

“On arriving here, I had a notion that I wanted to do something which might bring the peoples together.”

“I think that many misunderstandings that might exist are due largely to lack of contacts and interrelations.”

“I look forward to the day when the Koreans will take over; but we should see to it, that the schools are on a strong basis and well up to standard—no above the government’s [standard]…”

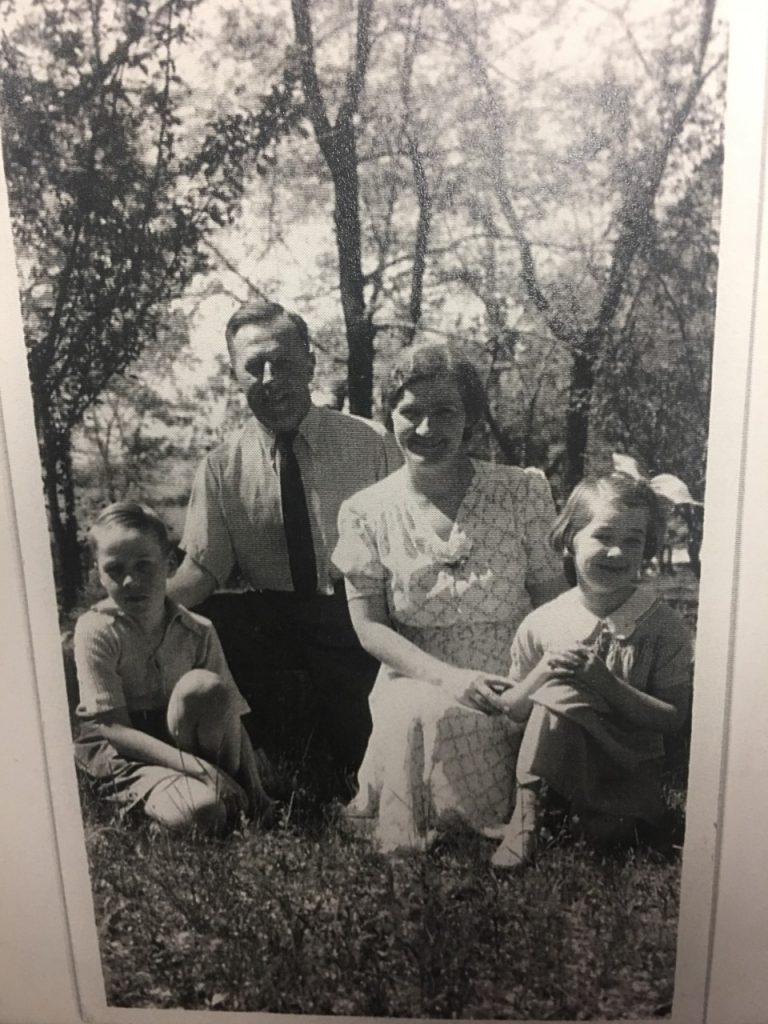

George was a man of relationships. He was a loving husband to Ellen, whom he endearingly called Nellie, and a father to Robert and Rena. His letters reveal his efforts to make the most comfortable living arrangement for his wife and his family’s hospitable reception of foreign missionaries. Even when he was temporarily separated from his family members, who stayed behind in Toronto after the furlough, he showed great care toward Ellen and did not rush her back to Korea. Ellen was also fond of Korea and was an adventurer and educator herself. She had grown up in Grand Valley, Ontario and during her teaching days, she went on exchange to London and took a bike trip with her friends to Southern Italy. In another one of her exchanges, she met George in Calgary, and they went on skating dates. For their wedding in 1925, George drove up from Calgary to Toronto with his four friends on a five-day trip.

“For some reason our home seems to be the place to which some single ladies want to come to have a little home life. If we can do the cause a little service in this way, it is surely a joy to us.”

George’s degree and experience in education were used to service others in Korea and Canada throughout his lifetime. While providing opportunities for others to learn, George continually sought out a place where he could learn. He looked into whether he could study theology on the field or during his furlough, and wanted to better equip himself by learning Japanese. After six and a half years in Korea and Manchuria, George took a furlough and studied at the University of Toronto, which resulted in a Bachelor of Pedagogy. Upon his return to Canada, George supervised a correspondence education project and headed 160 teachers within that branch of the Alberta government’s Department of Education. In 1962, he retired and moved to Toronto. A number of his pupils had also immigrated to various cities in Canada, and he kept in touch with them.

“I do object to intolerance.”

George and his experiences left an indelible mark on the progress of Korea and on his family members. In 1971, a group of graduates of the Eun Jin Academy invited George to Korea where he received the Korean Order of Merit from the Korean Government for his exceptional service in the education realm. His son, Robert Bruce, compiled letters written by his late father and letters addressed to him in hopes of putting together a biography. George’s great-granddaugther, on her trip to China, asked Robert for the coordinates to locate the Eun Jin Academy and found the school building still in place. Looking around the building, she was able to find her late great-grandfather in a photograph hung on the wall. Another one of George’s great-granddaughter is my friend, who knows how to say, “Quickly, quickly. (Ppalli Ppalli)” and “Let us pray. (Ki do hap si da)” in Korean. George’s love for learning, connections, and spirit of tolerance continues to live on in his family members and the generations of individuals indirectly touched by his work.

“Much could be written about events of those years. 1927-1941. They were interesting years, they were years of unrest when one could scarcely guess what the next day would bring; they were challenging years; they were years during which we formed close and lasting friendships with Korean, Japanese and Chinese Christians. They were years during which we strove to live lives of witness to the love of God for all men. However, we in turn learned much from those whom we sought to serve. Memories of those days are cherished by us and will remain with us to the end of the journey.”